I have been debating if I should cover Detroit: An American Autopsy by Charlie LeDuff on this site. At the surface, a book about the failure of a major American city doesn’t have much to do with IT supplier management or the other topics I cover on here (it could be a better fit at one of my other sites). But if you try hard enough, you can make some connections and come up with a few generalized life lessons.

So why did Detroit fail? Why does any organization fail?

They didn’t diversify and innovate.

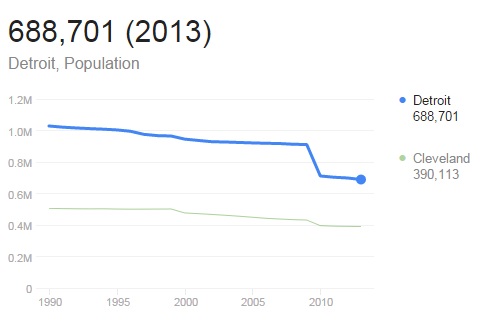

Detroit lived and died by the auto industry. When times were good and the factories were pumping out cars, the population of Detroit soared to over 1.4 million people. Migrant workers from all over the country and especially the south moved to Detroit for a better life, and they found it.

America enjoyed a wonderful and unnatural lack of automotive competition post WW2 (this part isn’t in the book). Germany was in ruins. So was Japan. American pride was at a high, so our grandfathers and fathers bought those Cadillacs. By the 1970’s fuel prices spiked for a time and those little Civics and VW Bugs were starting to make a whole lot of sense. The American car makers still tend to fumble with long lasting, fuel efficient cars (not all the time).

So the factories made less cars, tried to get the unions to adjust policy (good or bad), they pushed back, then the car companies moved jobs to factories in other countries.

Detroit had a slew of symbiotic businesses that flourished during the heyday. People opened their own factories that made car parts and chemicals and even catering services for the plants. Then the factories started buying cheaper parts and products from China.

By the time those small factories even thought to service international brands, it was already too late.

The jobs dried up. Working class families left. The city fell into disrepair without a tax base.

Now the people left don’t have the tools to protect or rebuild the city. Abandoned house are left to burn because fire fighters don’t have the right gear or enough men to keep up with the amount of arson. Children are asked to bring their own toilet paper to school.

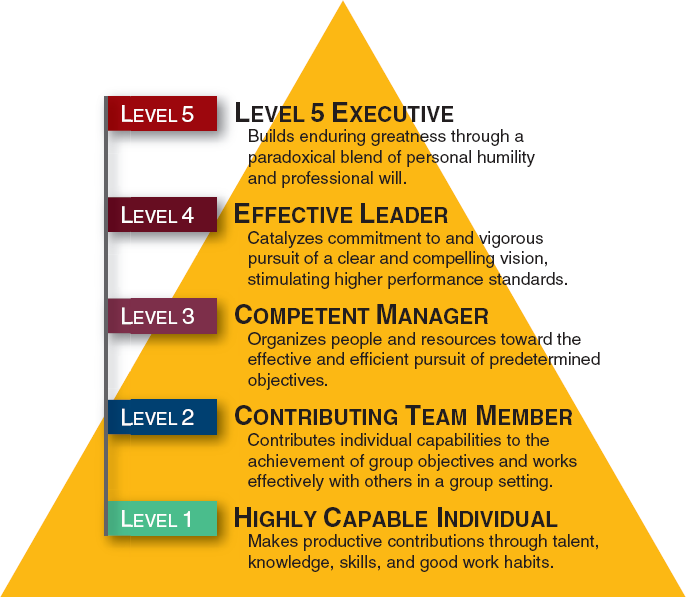

How does this compare to an organization or company?

You have to reinvest. In infrastructure, in people, in education. Things can fall into such a state of disrepair that an organization can never pull out (are we seeing that with HP?).

You have to have tight controls on where the money is going. Corruption is a considerably smaller problem in most corporations compared to government, but good companies still have money leaking out of places it shouldn’t. Money that can be reinvested.

You have to give people the tools they need to be successful and thus make the company successful.

People also need to have faith… that with hard work and a good plan, things will improve and ultimately flourish. The people of Detroit don’t seem to have faith that things will get better, so they are leaving. Detroit’s population is less than 700,000 people.

We have seen this happen to Camden, NJ on a smaller scale and I often wonder can this happen to Philadelphia? It almost happened in the 70’s. Factory jobs disappeared, the city’s blue collar workers struggled. But Philly turned it around by having an educational base (U. Penn, Drexel, Temple, La Salle), became a medical hub starting with CHOP, and some core financial and insurance companies made Philadelphia home (this is long before Comcast).

Here is a Ted X talk with author Charlie LeDuff (he uses colorful language so NSFWish):

Sometimes you can’t kick the can down road, you have to pick it up and deal with it now.